3387 阅读 2023-01-06 16:24:03 上传

专题研究二 走近乔姆斯基

[编者按]2022年9月20日,“读懂乔姆斯基”系列学术活动在北京语言大学拉开序幕,乔姆斯基教授通过网络平台全程在线参与,做了题为《读懂我们自己:论语言与思想》(Understanding Ourselves: On Language and Thought)的学术演讲,并参与了线上线下结合的“超越语言的边界:与大师面对面”(Language and Beyond: Web-Meeting with Chomsky)圆桌会议,回答了与会人员提出的问题。我刊特设本专题,刊发乔姆斯基演讲的中文稿和英文稿,圆桌会议答问录的中文稿,以及一篇与活动主题相关的综述性文章,为读者了解乔姆斯基语言学术思想在中国传播的主要路径提供一些线索。

读懂我们自己:

论语言与思想

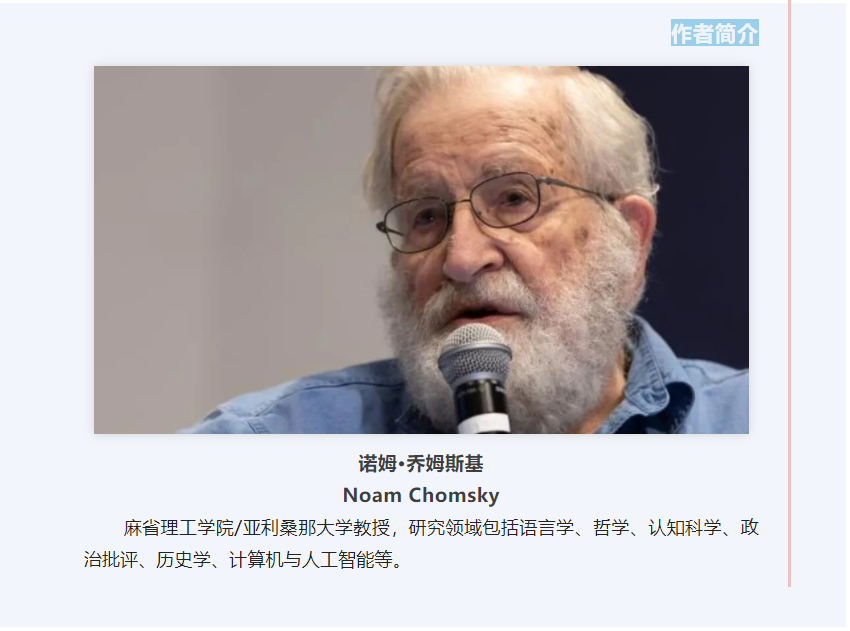

〔美〕诺姆·乔姆斯基1,2

司富珍3,时 仲3,赵欣宇3(译)

(1.麻省理工学院 语言学系 美国 波士顿 MA02139;2.亚利桑那大学 语言学系 美国 图森 AZ85721;3.北京语言大学 语言学系 北京 100083)

提 要 德尔斐神谕谕示我们要“认识自己”,这首先要重视我们作为同一物种的共同属性。语言与思想是将人类与其他物种区分开来的两个重要属性,而语言与思想具有等同关系:语言是生成思想的系统,思想则是由语言所生成的,它们为人类所共有,并且在重要的方面为人类所独有。回顾思想史和科学史上关于语言和思想的生成性、普遍性及创造性本质的认识,可以洞察科学家始终坚守着揭示复杂表象的简约性“神奇原则”。在此背景下,为了解决“人类语言的成就如何成为可能”这一“伽利略谜题”,可以引入关于语言研究的“强式最简主义”思路和关于词语指涉事物的“言语行为”观。当然,语言与思想并非人类的唯一特征。认识自己,关乎我们当前面临并且亟待化解的生存危机,关乎人类的未来。

关键词 语言;思想;强式最简主义;言语行为;“神奇原则”

一、引言:德尔斐神谕的启示

我们最好从头(即2500年前那个最早有详细记载的时期)说起:相传,德尔斐[1]在那时颁布了一道神谕,它定义了我们这个物种的主要任务——认识自己。

这个由两个词组成的格言警句“认识自己”可以从几个不同的方面得到解释。综合我们目前所知以及我们认识中最重要的方面来看,最合理的便是按照集体义来解释这一神谕:它是一则给我们人类集体的紧急忠告,敦促大家尝试去解读自身:读懂我们人类到底是何种生物。

而我们实际上是些奇异的动物,既是进化史上的骄傲,也是地球的祸害。想弄明白其中原因并非易事。但我们必须及时搞明白它,这样才有可能避祸就福。

人类出现的时间非常晚,大约在二三十万年前,在进化史上这不过是一眨眼的时间,因此我们之间差异非常有限,这一点也就毫不奇怪了。但是,人们总是觉得这些微小的差异至关重要,而对于共同之处则不把它们当回事。要读懂我们自己,正确的立场刚好相反:最为重要、最能揭示真相的恰好是我们之间的共同之处,它将我们与地球上所有其他的生命彻底区分开来。而我们之间的差异则只是表面现象。

这一点不仅在纯粹智力的层面上是成立的,而且从人类生活的角度看也是如此。放眼整个人类历史,我们正处于一个独特的时刻,要求我们必须迅速、果断地做出决定,否则人类社会是否还能以任何一种有组织的形式维持下去都会是个问题,这一点已经不是什么新闻了。当下危机交汇,关乎人类存亡。所有这些都是人类作为集体所共同面对的问题,不分你我。我们要么共同来回答这些问题,要么就什么都解决不了——这样的话人类实验将以不光彩的结局宣告结束。我后面还会就这个问题说几句。

所以我们有足够的理由将神谕所给予的忠告按集体义来释解:“我们到底是一群怎样的生物?”哪些是为人类所共有,而生命世界里的其他物种,包括那些属于人类近亲属的高等类人猿,却都不具有的物种属性?这就是被古人类学家称为“人类的能力”的属性。

在研究这个问题时,我想我们找到了符合这一严格标准的两个显著属性:语言和思想(至少是那些我们可以把握和学习的“思想”)。正是语言和思想使得人类能够去发布关于神谕的公告,去反思其意义,去为那些我们心智中被唤醒的问题寻找答案。而在人类最平凡的日常生活经历中,语言与思想也发挥着同样的作用。这些都为人类所共有,并且在重要的方面为人类所独有。

二、语言与思想研究中的“神奇原则”

如果研究表明语言和思想这两个具有区别性意义的属性实质上定义了我们这一物种,那么接下来的问题就是,它们之间有着怎样的关系。对此最简单的回答就是等同关系。语言是生成思想的系统,而思想是由语言所生成的。

而实际上这也正是在神谕发布的同时就给出的答案。在古印度,有一位著名的梵语学者巴特哈里,他是印度伟大的语法传统和哲学传统的奠基人之一。在他的概念里,“语言不是意义的载体或思想的传递者”,而是它的生成原则:“思想锚定语言,语言锚定思想……使用语言就是在思想,思想则通过语言而‘振荡’。”

类似的观点在思想史上不断回荡。16世纪时西班牙医学哲学家胡安·瓦尔特就强调人类理解力中那个为人类所独有的特性,他称之为“生成品质”:这是一种我们在正常生活中一直使用的能力,我们用语言建构新思想,并且还用语言去理解他人的思想。这为不久之后发生的第一次认知革命奠定了基础。瓦尔特还发现了另外一种更高形式的才智,这种才智使得某一些人得以创造具有真正智力水平和审美价值的作品,而其他像我们这样缺乏这种天赋的人,则至少可以享受它、欣赏它,有时候还可以继承它并发扬光大。这是我们物种的另外一种属性,它可能是由语言-思想的复合体派生而来的。

瓦尔特也坚持关于语言结构普遍性的观点,认为大脑是认知功能的物质场所,同时他还坚持认为这些认知功能具有天赋性。随着对人类理解力这一生成品质认识的加深,这些思想复活了,它们是在人们对久已被遗忘的历史一无所知的情况下复活的,是在1950年代被称作“认知革命”的运动中复活的,是在与当时盛极一时的结构主义-行为主义教条的断然决裂中复活的。

这些思想曾经繁荣于17世纪科学革命期间,并为现代科学奠定了基础。而那次革命的核心部分则是,科学家们都愿意沉迷于对简单的事情的思考,虽然一般人常常认为这些事是理所当然的。为什么石头会向地球落下,而蒸汽则会离开地面向上升腾?为什么我们会把某些视觉呈现的东西看成三角形?伽利略和他同时代的人们不满足于用“神秘思想”去解释世界上发生的事情。他们希望将注意力集中在简单的现象上,并为它们寻求解释。这种研究思路如同孩子不断地追问为什么。这一立场此后一直推动着人类理解向前发展。

伽利略认为自然是简单的,而科学家的任务则是揭示自然的这一简单性。对伽利略来说,这是一种指导研究工作的理想。在随后的若干年里,人们发现这一点在许多领域都是正确的,它也因此成为一种坚定信念——即阿尔伯特·爱因斯坦所说的“神奇原则”(Miracle Creed),用他的话说就是“一条屡试屡验到令人惊讶程度的神奇原则”。

语言也没有逃过现代科学奠基者们的法眼。伽利略及其同时代人曾表达过他们对一个非凡事实的敬畏和好奇:只需要几个符号,我们每个人就都可以在我们的头脑里建构出无限的思想来,还可以在对方不进入我们大脑的情况下把我们思维中最为内在的部分传达给他们。对笛卡尔来说,语言通常所具有的创造性使用的特点是他所说的第二物质(即思维,res cogitans)的基础,它将语言与思想联系起来,是一种独属于人类的物质。伽利略认为,字母表是人类最令人叹为观止的发明,因为它捕获到了语言的这一奇迹。

几个世纪后,现代逻辑和逻辑哲学的奠基人戈特洛布·弗雷格也回应了伽利略发出的这一惊叹。弗雷格发现:“语言的成就令人惊讶。它用几个音节表达了无数的思想,甚至对于一种人类首次掌握的思想来说,它也为之提供外衣,这样,对它一无所知的其他人也能够认识它。”

这些伟大的思想家对人类语言如此惊叹是完全在理的,正如他们一直坚持对那些看似平淡无奇、不言而喻的事情保持疑问一样。仔细观察就会发现,这些事情看似平淡无奇、不言而喻,实际却并非如此。

三、语言与思想的“伽利略谜题”

关于语言和思想的这一洞察引出了一个我们称之为“伽利略谜题”的问题:人类语言的这一成就何以成为可能?在我看来,这个伽利略谜题似乎清楚地抓住了在探究语言和思想的本质(它事实上是人类独特的本质)方面所面临的主要任务。

正是这一伽利略谜题催生了普遍唯理语法的丰富传统。说它“普遍”,是因为它寻求人类语言的普遍原则;称之曰“唯理”,是因为它试图超越描写的局限,而去寻求解释。在这一传统中,人们始终普遍认为语言与思想紧紧地捆绑在一起。19世纪时的语言学家威廉·德怀特·惠特尼曾用一句简单的话表达了这种共识,即语言是有声的思想——尽管我们现在认识到声音并非占据那么独一无二的地位;其他感官模式也可以起到同样的作用。伟大的人文主义者、现代研究型大学的创始人威廉·冯·洪堡特进一步将语言与思想等同起来,把语言描述为“一种生成活动”,并对如下事实进行了深入思索,即,语言的这种生成活动可以“将有限手段无限地使用”,而这正是伽利略谜题的一个基本特征。

洪堡特对伽利略谜题的表述揭示了以往整个研究传统中的一个严重缺憾,即,未能考虑到亚里士多德对拥有知识和使用知识(用当代的话来说就是对语言能力和语言运用)所做的关键区分:以往的传统一直专注于使用知识的方面,更具体地说,就是专注于言语产出中的知识使用问题,却很少提及语言感知问题,然而语言感知是现代心理语言学的首要关注点。而感知和产出都可以触及人们内在拥有的知识。

那时还没有合适的工具用来清楚地制定和实施如下基本任务:揭示所拥有的知识体系,这个知识体系用现代技术性的说法来表达就是内在语言或I-语言。

上述这一缺憾被阿兰·图灵以及20世纪早期其他一些伟大的数学家所创造的现代计算理论弥补了。他们重塑了这一传统。这些工具使人们得以重新认识曾被遗忘的亚里士多德对拥有知识和使用知识所做的区分,也第一次使得人们对“拥有的知识”展开认真研究成为可能。同时,他们也使得“一个有限的机制是如何产生无限的输出结果的”这一问题变得清晰起来。当然他们也并没有完全解决洪堡特关于言语产出的困惑,但它使我们有可能开辟出可行的研究领域来,即研究人们所拥有的知识的生成问题:手段有限,但范围却无限。而语言的产出,就像其他创造性活动一样,无论在任何基本意义上都无法探究,它如同简单自发行为一般难解。

语言的生成和产出之间的区别是一个根本性的问题,但恰恰也是经常被误解的问题。语言生成性划定了语言的地盘,它包括了语言所建构的所有思想,无穷无尽。而语言产出则是使用这些语言所建构的思想的一种活动,并且这些活动通常是以人们还不理解的创新性和创造性方式进行。用笛卡尔的术语来说,我们对语言的使用是适应环境的,而非由环境引起的。我们被引导并倾向于以某种方式说话,但却并不是被强迫这么做。而瓦尔特意义上的更高形式的创造力则更为神秘。

上面提到的这种计算理论作为新工具,使我们首次有可能发展出一种关于语言的解释性理论,这种语言可以产生无限的、由层级结构所构成的表达,而这些结构则用来建构思想,并且可以通过感官运动媒介(通常是声音)来得到外化——这一点可以称作语言的基本属性。

这项事业一经着手便暴露出了问题。当时占统治地位的结构主义-行为主义理论所达成的共识中并没有什么真正的不解之谜,似乎所有根本的东西都已知晓;各种分析程序可用于任何材料的语料库,从而产出结构描述。正如美国著名语言学家雷纳德·布龙菲尔德所提出的那个广为接受的理论教条:语言习得被理解成仅仅是训练和习惯的问题。

而当寻求解释的努力一旦开始,就发现实际上几乎什么都不知道。几乎每一句话都会带来新的困惑。而且,在他们关于研究程序的时间表里也找不到任何构成最佳解释理论应该有的基本要素;而在其他科学分支中,重要的理论要素是一定会列入工作程序的时间表里的。寻找最佳理论是一项创造性的活动,这种努力无法通过算法来实现。

四、关于语言的强式最简主义解释方案

对于语言来说,解释必须从两个层面进行。关于某一种语言的生成语法应该是一种试图解释该语言属性的理论,而语言的属性即指语言使用者所拥有的知识。在更深层次上,关于人类所共享的语言官能的理论关注的是使语言习得成为可能的先天因素,这些先天因素将人类与所有其他有机体区别开来。用现代术语来说就叫做“普遍语法”(universal grammar,UG),这是一个由传统术语改编而来并融入新的理论框架中的概念。

UG似乎有着相互矛盾的若干目标,它必须满足至少3个方面的条件:

(i)首先,UG必须足够丰富,以克服刺激的贫乏性(poverty of stimulus,POS)问题:事实上,所获得的知识明显远远超出能够接触到的可用证据的范围。这是有时被称作为“柏拉图问题”的一个特例。正如伯特兰·罗素所言,我们为什么能在证据如此少的情况下懂得这么多?

(ii)同时,UG又必须足够简单,它是在人类进化所提供的种种条件下进化而来的——这点有时被称作“达尔文问题”。

(iii)UG对于所有可能的语言一定是相同的,它是一种固定不变的人类物种属性。这一点是必然的,因为事实上不存在只针对特定语言的生物适应机制。

只有把研究重点限制在可以同时满足可学性、进化性和普遍性的共同机制上,我们才能对某些语言现象提供真正的解释,尽管这三者之间看起来存在矛盾。也正是调和相互冲突的需求这一目标在推动着理论探求的发展进程。

早在生成语法初期,这些问题就已经显现。而现在我们才知道,问题的严重性远超我们当时的预期。

就进化性而言,有关基因的研究表明,人类在出现后不久就开始分化。语言官能是先天存在的,就目前所知,人类之间并无区别。此外,也没有充分的证据支持符号的使用存在于智人(现代人类)出现之前。这些事实说明,语言与现代人类几乎同时出现。如果这一结论正确,我们就会认为语言的基本结构应该是相当简单的。这是人类始祖大脑内部曾经发生的某种相对来说小型的线路重组的结果,它一经发生,至今未曾改变。因此,这与可学性之间的明显矛盾变得更加尖锐。

语言习得领域的研究进一步加剧了这一困境。研究表明,两三岁的孩子已经大致掌握了其语言的基本特性,包括一些显著特征。此外,对儿童实际获得的数据的统计学研究表明,孩子所获得的相关证据非常稀少。这些发现似乎要求UG必须非常丰富,以解决稀少的可用数据和获得的丰富知识之间的巨大差距带来的问题。然而,进化条件则又要求UG是非常有限的。再加上其后还有数量上显然无穷无尽的变体问题。

在过去的一些年里,最简方案让我们看到解决这一纠结困境的希望。想了解它是如何做到这一点的,我们可以来看一下结构依存性这一语言的最基本的也是最费解的普遍属性。

先来想一想下面这个简单句的特性。实验结果表明,两岁的孩子就已经能够掌握它:

(1)The boy and the girl are in the room.

这里用的是“are in the room”,而不是“is in the room”。

这一现象让人困惑。要确定一致性问题,儿童依靠的并不是邻接原则这一最简单的计算规则,相反,他本能地依赖于某种他从未听到过的规则:他依赖的是其大脑创造的结构。接着,孩子依据这个抽象结构的本质为句子指派复数形式。

这个问题很容易得到延伸。请看以下句子:

(2)a. The friend of my brothers was happy.

b. The friends of my brother were happy.

在决定是使用was还是were时,我们忽略线性上的邻接关系,只关注那个由名词短语做主语的结构。不仅如此,还必须更进一步去寻找这个名词短语中的中心成分friend/friends,即那个线性距离上更远一些的名词。结果证明这一计算过程并非微不足道,它远比线性邻接规则复杂,但更加简单的线性邻接规则却被本能地忽略了。

接下来,让我们更进一步。“The mechanic who fixed the car carefully packed his tools”是一个有歧义的句子:可以解读为“fixed the car carefully”(小心地修理汽车)或者“carefully packed his tools”(小心地打包工具)。现在,把副词carefully(小心地)放在前面:“Carefully, the mechanic who fixed the car packed his tools”这个句子的含义就变得明确了,意为他小心地打包了工具。副词carefully需要寻找一个动词,但它却不能使用最简单的计算过程:选择线性距离最近的动词。UG迫使我们忽略简单的计算,而选择线性距离更远的动词——当我们按照大脑告诉我们的正确方式指派结构时,我们就会发现这恰好是结构上距离最近的动词。

毋庸置疑,这些都不可能是后天学到的。

神经语言学中有证据支持这一观点。实验表明,如果向被试展示根据真实语言建模的人造语言,大脑中语言区的反应是正常的;但是,如果人造语言使用线性顺序等非常简单的规则,这时大脑中出现的扩散性活动则表明,大脑将这种人造语言视作谜题进行处理,此时语言区就不会被激活。

因此,我们就会产生一个严重的困惑:婴儿明明听到的是线性顺序,但却将其尽数忽略,而只关注他从未听到的那些由大脑所构建的抽象结构。而且,这一点适用于所有语言中的所有结构。

那么,看来唯一合理的答案就是,线性顺序对正在习得构建思想系统的孩子来说还没有什么用。但如果是这样,为什么语音上还需要线性化呢?原因显而易见。发音系统无法产出结构,所以外化程序就必须把线性顺序强加于生成思想的内在系统上,而实际上内在系统其实并非是按线性顺序排列的。手语在线条性上就不那么严格,因为运用手语时在视觉空间中有更多的选择。

用于外化的感觉-运动系统(Sensory-Motor System)与语言无关;它们早在语言出现之前就存在了,而且从那时起就没有改变过。真正的语言是产生思想的内部系统I-语言,它对于个体来说是内在的,在大脑中编码为递归的生成程序。

我们现在面临的问题是,为什么婴儿听到的是线性顺序,却本能地将其百分之百地忽略,而只关注他从未听到的、由大脑构建的抽象结构。

我们近期发现,对此有一个直截了当的答案。那就是,要满足“基本属性”就需要一个计算程序。而最简单的程序则是二分的固定形式,它在最近的研究中被称作“合并”(Merge)。如果递归生成是基于“合并”程序,那么结构依存性就是强制性的,因此也就不存在线性顺序,这一点很容易证明。在这方面,语言符合那个“神奇原则”,即去寻找最简单的解决方案。

这会产生多方面的影响。其中影响之一是,某些思想在言语中变得难以表达,有时即使非常简单的思想也可能如此。为了说明这一点,让我们把注意力从合取式并列结构转到析取式结构上来。比如“Either John or Mary is in the room”以及“Either the girls or the boys are in the room”这两个句子。我们来看看,这个结构如果是“Either the girls or John [is] in the room”或“Either the girls or John [are] in the room”情况会是怎样的呢?这时你会发现这两种结构都不可能。句子想要表达的思想很清楚,而如果数的一致关系是基于线性上的邻接关系,那表达应该不会存在问题。但考虑到结构依存性,这个思想内容就无法用最简单的方式表达出来了,因为在这个析取结构中存在着内部冲突。

这只是最佳设计和沟通效用之间存在冲突的众多例子之一,还有许多例子问题更加严重,而解决这些问题的方式却总是相同的:那就是,总是牺牲沟通效用。打个比方,大自然母亲在构建语言时关心的是最佳设计,而不是如何使用这个系统。所以如果语言有时功能缺失,那也只能由它去了。

值得注意的是,这是物种进化的普遍方式。我们可以区分一般进化演变的3个阶段。第一个阶段是革新阶段。某些基因发生了破裂,有可能是基因突变或者基因转移,或者个别细菌意外吞食某种微生物从而变成真核细胞,也就是复杂生命的基础形态。所以是基因破裂带来了新生事物。接下来就到了第二个阶段,即重构阶段:大自然以最简约的方式重新设计出一套满足自然法则的新系统。这些在达西·汤普森关于万物生长法则以及阿兰·图灵关于自然法则下斑图[2]形成机制的经典著作中曾有过深入的探讨。这同样也是“神奇原则”的再现。进化的第三个也是最后一个阶段是筛选阶段:自然选择使得物种的多样性有所减少,那些适应性更强的生物种类生存了下来。由上一个进化阶段所产生的最简策略或许会存在功能缺失之处,但大自然对此并不介意。在重构的过程中,大自然寻求的是最佳设计,而无法顾及它有哪些可能的功用。

语言似乎也符合这种一般的进化模式。可以设想一种与之相仿的进化情景:大脑中的某个部位发生了线路重组,它带来了递归生成的普遍属性。随后大自然依照通常的做法,运用自然法则(具体到这里的讨论就是计算效率原则,因为我们正在讨论计算系统的问题)去寻求一种最简操作。结果是,大自然寻求到的是一种基于合并的系统,它满足语言的基本属性的需要。紧接着就出现了语言最深层次、同时也是最让人感到意外的一个属性——结构依存性,同时也带来了一系列后果。这些内容又经由普遍语法进行编码加工。正因如此,婴儿会本能地忽略掉耳朵里听到的一切,而只在意自己大脑中创造出来的抽象结构,并最终把它充实为思想。

据此,我们可以为普遍语法所面临的难题设想一种解决方案:在研究思想生成的核心系统时,可以暂且将多样性条件[3](条件iii)搁置一旁。语言的多样性可能很大程度上是在词汇的边缘层面以及语言外化层面产生的;或许有朝一日,我们能够获知,事实上多样性全部都是在这些层面产生的。而在我看来,目前的研究正朝着这个趋势发展,这也将会是一个自然而然的结论。而刺激贫乏性之于核心系统来说则非常严苛、无法跨越,就像上面谈到的结构依存的情况那样。此外,感觉-运动和I-语言的关系也引出了很多认知方面的问题,这些问题可以通过多种方式解决。如果结论表明语言的复杂性、易变性以及多样性的核心原因即在于此,那应该也就并不奇怪了。这些想法如果没错,那么所有这些语言的复杂性、易变性和多样性问题就都只是些表面现象罢了。

倘若如此,至少对于I-语言来说,难题就被大大简化了,只要满足进化性条件(条件ii)就足够了。只要I-语言的结构由最简操作生成而来,问题便迎刃而解。这也是强式最简主义(Strong Minimalist Thesis,SMT)为语言理论设立的首要目标。其假设内容是,语言在构建思想的核心属性方面,与大自然的其余组成部分一样,同样符合“神奇原则”。

上述观察结论印证了一种传统观念,即语言从本质上讲是一个关于思想的系统。而那个关于语言根本上是一个可能从动物交际演化而来的交际系统的现代教条看来是站不住脚的。

再回到进化的情景上来。进化史的第三个阶段,即筛选阶段,其实目前的研究显然还从未触及。不过,看起来筛选的结果是语言之间似乎没有什么差异,这一点应该是对的。之所以没有差异,或许是因为进化时间还太短,抑或是因为整个系统结合得太过紧密而无法分开,因此筛选的结果是要么全有、要么全无,这很有趣。这点得到越来越多复杂案例的印证。

五、关于词语指涉事物的“言语行为”说

与其继续讨论更多关于可信性解释的案例,接下来不如换个话题,探讨思想是如何在头脑中丰盈起来的。

I-语言是一个计算系统。任何一个这样的计算系统都会有原始元素(即用于计算的原子成分)以及用于生成新元素的计算程序。

对语言来说,这些原始元素就是最小的“有意义的”成分,在类似英语这样的分析性语言中通常就是单词。所以我们才会看到《词语和对象》(W. V.蒯因)或《词语和事物》(罗杰·布朗)这类标题的书籍。而对于一般意义的语言来说,原始元素并不是单词。甚至如果我们仔细观察,会发现英语同样如此,不过这里暂且不做详细讨论。

这些书名反映出一种主流观点,即词语指涉世界上的事物,且词语与外部事物通过指称关系建立联系。对于科学界来说,建立这样一种对应关系是一种规范做法。当科学家们谈到“铀”或“基因”时,他们希望确实存在这些东西。动物的交际系统看上去也遵守这些条件,它们发出的信号(例如猴子的叫声)和某种物理上可识别的事件之间存在一一对应的关系。但很多证据表明,指称说在人类语言中并不成立。我们的确会使用词语来指代某些事物,但那体现的是一种行为,也就是英国哲学家约翰·奥斯汀所说的言语行为。而如果我们仔细研究词语的含义,就会对词-物对应的观点产生质疑。

哲学文献中常常以一个假定的逻辑专名(logically proper name)为例,比如“伦敦”。伦敦曾被一场大火烧毁,而后又在泰晤士河上游50英里处重建,所用的材料和设计风格与此前截然不同。但我仍然完全可以说,我打算再去参观一次伦敦。没有人相信有现实世界中的某个实体具有这样的属性。实际上,“伦敦”并不是一个专有名词,而只是一个城市的名称。“城市”作为一种心理概念则具备更为丰富、复杂的属性,在使用“伦敦”一词进行指代性的言语行为时,这些属性就会被传递下去。

上述观察结论可以扩展到全部词汇,这与亚里士多德所持观点相仿。他在讨论“房子”一词时观察到,房子其实是一种物质和形式的混合体。物质部分即物理学家可以辨别的东西,如砖头、木材等。其形式则是一种精神层面的构造:设计上的规划构思、建筑师的意图想法、特色的功能用途等等。某个物体可能看起来和我的房子一模一样,但它实际上是个图书馆,或者车库,又或是巨人的镇纸,而这些属性都无法通过物理手段检测到。

在亚里士多德之前,希腊哲学家赫拉克利特也表达过类似的观点。他问道,如果一条河流的物质成分发生改变,我们又如何能够两次踏进同一条河流?这是一个很深奥的问题。但稍加思考就会发现:从上文提到的“言语行为”的角度看,如果河流的物质变化较为猛烈,那么它指的仍然是同一条河流;反而是,如果只发生细小轻微的变化,它就不能称作河流,而可能是水道,或者是表面硬化的什么东西,甚至可能是公路。其他用来指代事物的最简单的词汇道理也是如此。

语言和思想的这些特征又引出了新的难题,即,上述这些知识都必须不假学习便可知晓,并且还应当在最根本的方面具备跨语言的共性。语言习得研究表明,在这些知识的习得过程中呈现给习得者的外部材料少之又少,这意味着,习得过程主要依靠的是一套丰富的天赋而来的结构。而学习的过程显然就是把语言相对表面的那些属性设置好的过程。而在动物符号系统中,并不存在非常相似的概念。当然也没有任何关于它们这方面发展的记录。

出于以上原因,人类概念的起源似乎是一个无望破解的神秘谜题,它深埋在智人的史前时代。但仔细想想又不是这样。作为计算的原子成分,这些丰富繁多而又错综复杂的概念,假如游离于那个能够产生进入推理、思考和其他心理行为的复杂表达的、生成思想的语言系统之外,它们将百无一用。倘若概念先于语言出现,它们将被视为无用的废物而被弃置。因此,一个合理假设是:语言表达的递归生成能力出现后,取代了原始人类用于表达基本概念的词汇;后来,随着生成语言和思想的组合可能性的出现,具有独特人类特征的概念才正式登场。具体过程我们无从知晓,但至少可以就这个问题展开探索。

强式最简主义在这里再次发挥作用。当某种进化创新出现时,大自然会寻求最简约的方式来进行适应。参与进来的因素越简单,所产生的系统就越精细。介入的因素过多,后果可能就会变得混乱不堪。可以想象,概念作为人类思想的独特资源,强式最简主义的简约性和严律性在其发展过程中起到了举足轻重的作用。人类在数万年的历史上形成了丰富而有创造力的生活以及复杂多样的社会秩序,随着这些更多地为人们所了解,也会有更多新颖、有益的见解进入人们的视野。而这将是举世欢欣之事。

六、余论:认识自己与人类未来

沿着上述路径,我们或许能够真正洞察到语言和思想的本质,也就是人类能力的最根本特征。当然,这不是我们唯一的特征。环顾四周就会发觉,作为一种出现在地球上没多久的奇异生物,人类的身上还具备其他一些引人注目的特征,在一开始我就提到过。它们关乎我们当前面临并且亟待化解的生存危机。

77年前的1945年8月6日[4],这一议题以一种激烈的形式清晰地呈现在世人面前。自那一天起,我们认识到人类的智慧已经达到了可以摧毁全世界的程度——实际那时还未达到,但那时显然就很清楚地表明,对人类的科学技术来说用不了多久就可以做到这点。后来事实上确实也仅在1952年便达到了这个水平:那一年,美国第一枚热核武器爆炸,没过多久,苏联也同样做到了。

这引出了一个关于人性的深刻问题:我们的道德能力是否足以驾驭我们的毁灭能力?从随后几年的观察来看,情况并不乐观,在核武器之外的方面同样如此。1945年时的人们还未察觉到,地球正在进入一个新的地质年代,即人类世,一个人类活动对环境造成严重影响的时代。这些影响已经危及我们这些有组织的人类的生存命运,更不用提那些正在被我们肆意毁掉的大量物种了。

地质学的国际权威组织将人类世的开始时间界定在第二次世界大战后。自那时起,人类对地球的破坏急剧升级,现在情况已经达到了不可逆转、一触即发的地步。

随着时间的推移,这一问题变得愈加凸显和尖锐。人类所掌握的破坏能力和控制破坏冲动的道德能力之间存在着一定的差距。问题是,这个差距能被消除吗?我们很快就会发现,如果选错了答案,其他的事情就都不重要了。

注释:

* 该演讲稿的中英文摘要、关键词和二级标题为译者所拟。——译者注

[1] 古希腊重镇,阿波罗神庙所在地。——译者注

[2] 即图灵斑图,指自然界中所呈现的不断重复、周期性排列的图案,如猎豹的斑点、斑马的条纹、贝壳的纹路。——译者注

[3] 即前文提到的“普遍性条件”,普遍性与多样性实际上是一个问题的两个方面。——译者注

[4] 1945年8月6日,美军向日本广岛投掷了原子弹,核武器首次被用于人类战争。——译者注

Noam Chomsky

1. Introduction: Enlightenment from the Delphic Oracle

A good place to begin is at the beginning, 2500 years ago, about as far back as detailed records go. That is when the Delphic Oracle issued a pronouncement defining our primary task: Know Thyself.

A two-word aphorism can be interpreted in many ways. Given what we know today, and what should be uppermost in our minds, a reasonable way to interpret the Oracle is in collective terms: as urgent advice to try to understand what kind of creatures we humans are.

And we are indeed strange beasts, at once the pride of evolutionary history and the scourge of the earth. It’s a challenge to find out how this could be. And an imperative to find out in time so that we can fend off the worst and aspire to the best.

Humans appeared very recently, some 2-300,000 years ago, a blink of an eye in evolutionary time. Not surprisingly, there is very limited diversity among us. The slight differences are what matter for life; the commonalities we take for granted. For understanding ourselves, the proper stance is the exact opposite: What is deeply important and most revealing is what is common to us, what distinguishes humans so radically from all other life on earth. Variation is superficial.

That much is true on pure intellectual grounds, but also in its import for human life. It is not news that we are at a unique moment in human history, a moment when decisions have to be made, quickly and decisively, as to whether human society will persist in any organized form. We are living at a moment of confluence of severe crises, existential ones. All are collective, with no boundaries. We will answer them together, or not at all, in which case the human experiment will come to an inglorious end. I’ll return at the end to a few words on that.

For good reasons, then, we should interpret the advice of the Oracle collectively: What Kind of Creatures are We? What are the species properties that are common to humans apart from severe pathology, and are without significant analogue elsewhere in the living world, even among our closest relatives the higher apes? These are the properties that paleoanthropologists call “the human capacity”.

When we inquire into this question, I think we find two striking properties that satisfy this austere criterion: language and thought—at least thought in any sense that we can grasp and can study. It is language and thought that enable humans to issue the proclamation of the Oracle, to reflect on its meaning, to seek to find answers to the questions it awakens in our minds. And the same is true of the most mundane experiences of ordinary human life, all common to humans and in important ways distinctive to the human species.

2. “Miracle Creed” in the study of language and thought

If inquiry reveals two distinct properties that virtually define the species, the next question is what relation holds between them. The simplest answer would be the relation of identity. Language is a system for generating thought, and thought is what is generated by language.

That in fact is the answer that was given at about the same time as the pronouncement of the Oracle: in classical India by a famous Sanskrit scholar, Bhartrhari, one of the founders of the great tradition of Indian grammar and philosophy. In his conception, “language is not the vehicle of meaning or the conveyor of thought” but rather its generative principle: “thought anchors language and language anchors thought… using language is thinking, and thought ‘vibrates’ through language.”

Similar ideas resonate through intellectual history. The 16th century Spanish physician-philosopher Juan Huarte set the stage for the first cognitive revolution that followed shortly after by emphasizing what he called “the generative quality” of human understanding, unique to humans: the capacity that we constantly exercise in normal life in using language to construct new thoughts and to interpret those of others. Huarte also identified a still higher form of intelligence that enables some to create work of true intellectual and aesthetic value—while the rest of us, lacking this talent, are at least able to enjoy and appreciate it, sometimes to carry it forward, another species property that probably derives from the language-thought complex.

Huarte also insisted upon the universality of language structure, on the brain as the material site for cognitive functions, and on the innateness of these functions. Along with the generative quality of human understanding, these ideas have been revived, without any awareness of the long-forgotten history, in what is called “the cognitive revolution” of the 1950s, in a sharp break from then-prevailing structuralist-behaviorist doctrines.

These ideas flourished during the 17th century scientific revolution, which laid the basis for modern science. A core part of the revolution was the willingness to be puzzled about simple things, ordinarily just taken for granted. Why do rocks fall the earth while steam rises? Why do we see a certain visual presentation as a triangle. Galileo and his contemporaries were not satisfied with the “occult ideas” that were invoked to account for what happens in the world, and wanted to focus attention on simple phenomena and find explanations for them. Much as children do with their incessant why-questions. That’s the stance that has always driven understanding forward.

Galileo held that nature is simple and it is the task of the scientist to demonstrate that. For Galileo, it was an ideal to guide research. In the centuries that followed it has been found to be true in so many domains that it has become a firm belief—what Albert Einstein called a “miracle creed”. In his words, “a miracle creed which has been borne out to an amazing extent by the development of science”.

Language did not escape the attention of the founders of modern science. Galileo and his contemporaries

expressed their awe and wonder about a truly remarkable fact: with a few symbols, each of us can construct infinitely many thoughts in our minds, and can convey to others with no access to our minds their most innermost workings. For Descartes, the normal creative use of language, employing this capacity, was a foundation for his postulating a second substance, res cogitans, relating language and thought, a substance unique to humans. Galileo himself

regarded the alphabet as the most spectacular of human inventions because it captured this marvel.

Galileo’s amazement was echoed centuries later by Gottlob Frege, the founder of modern logic and logical philosophy. Frege found “astonishing what language accomplishes. With a few syllables it expresses a countless number of thoughts, and even for a thought grasped for the first time by a human it provides a clothing in which it can be recognized by another to whom it is entirely new.”

The amazement of these great thinkers is entirely warranted. As is their insistence on puzzlement over what seems commonplace and self-evident. It rarely is, when we look closely.

3. “The Galilean Challenge”

The insight about language and thought poses what we may call “the Galilean challenge”: How is this achievement possible? The challenge seems to me to capture lucidly the major task faced by the inquiry into the nature of language and thought, in fact into the unique nature of the human species.

The Galilean challenge initiated the rich tradition of General and Rational grammar, general because it sought universal principles underlying human languages, rational because it sought to go beyond description to explanation. Throughout, language was generally regarded as closely bound to thought. The common understanding was captured simply in the phrase of the 19th century linguist William Dwight Whitney that language is audible thought—though we now recognize that sound does not have that unique status; other sensory modalities will do. The great humanist and founder of the modern research university Wilhelm von Humboldt, went further. He identified language with thought. He characterized language as “a generative activity” and he pondered the fact that somehow this activity “makes infinite use of finite means”—a basic feature of the Galilean challenge.

Humboldt’s formulation of the Galilean challenge brings to light a serious gap in the entire tradition. It failed to accommodate Aristotle’s crucial distinction between possession of knowledge and use of knowledge; in contemporary terms, between competence and performance. The tradition kept to use of knowledge, more specifically, use of knowledge in production of speech. Little was said about perception of language, a prime concern of modern psycholinguistics. Both perception and production access the knowledge that is internally possessed.

Appropriate means were not available to formulate clearly and pursue the fundamental task: to unearth the system of knowledge possessed, the internal language, I-language in modern technical usage.

This gap was overcome by the modern theory of computation created by Alan Turing and other great early 20th century mathematicians and adopted in the modern reshaping of the tradition. These tools made it possible to resurrect Aristotle’s forgotten distinction between possession and use of knowledge and to launch serious study of possession of knowledge for the first time. They also made it clear how a finite mechanism can have infinite output. That does not entirely resolve Humboldt’s puzzle about production, but it makes it possible to carve out the domain of feasible inquiry: the study of generation of the knowledge possessed, with finite means and infinite scope. Production of language, like other creative activity, is beyond reach of inquiry in any fundamental sense, as is even simple voluntary action.

The distinction between generation and production of language is fundamental, and commonly misunderstood. Generation lays out the terrain: here are the linguistically-formulated thoughts, the whole infinite range of them. Production is an activity that makes use of these thoughts, commonly in innovative and creative ways that are not understood. In Cartesian terms, our use of language is appropriate to circumstances but not caused by them. We are incited and inclined to speak in certain ways, but not compelled. And Huarte’s higher form of creativity is still more mysterious.

The new tools of the theory of computation made it possible for the first time to develop explanatory theories of a language that yield an infinite array of hierarchically structured expressions that constitute thought, and can be externalized in some sensory-motor medium, usually sound—what we can call the Basic Property of Language.

As soon as this enterprise was undertaken, problems arose. The reigning structuralist-behaviorist consensus had no real puzzles. Everything essential was known; procedures of analysis could be applied to any corpus of materials, yielding a structural description. Acquisition of language was understood to be just a matter of training and habit, as the leading American linguist, Leonard Bloomfield, formulated widely accepted doctrine.

As soon as the search for explanation began, it turned out that almost nothing was known. Virtually every sentence poses new puzzles. Furthermore, the elements that were postulated in the best explanatory theories could not possibly be found by a schedule of procedures, just as in every other branch of science. Search for the best theory is a creative activity. There are no algorithms for such endeavors.

4. The Strong Minimalist Thesis

Explanation in the language case has to proceed at two levels. A generative grammar of a language is a theory that seeks to account for its properties, the knowledge possessed by the language user. At a deeper level, the theory of the shared language faculty is concerned with the innate factors that make language acquisition possible—factors that distinguish humans from all other organisms. In modern terms, it’s called universal grammar, UG, adapting a traditional term to a new framework.

UG has goals that appear contradictory. It must meet at least three conditions:

(i) UG must be rich enough to overcome the problem of poverty of stimulus (POS), the fact that what is acquired demonstrably lies far beyond the evidence available. This is a special case of what is sometimes called “Plato’s problem”; as formulated by Bertrand Russell, how can we know so much with so little evidence?

(ii) UG must be simple enough to have evolved under the conditions of human evolution—sometimes called “Darwin’s problem”.

(iii) UG must be the same for all possible languages, a fixed human species property. It’s necessary given the fact that there is no biological adaptation to specific languages.

We achieve a genuine explanation of some linguistic phenomenon only if it keeps to mechanisms that satisfy the joint conditions of learnability, evolvability, and universality, which appear to be at odds. The course of theoretical inquiry has been driven by the goal of reconciling these conflicting requirements.

These problems were evident at the outset of the generative enterprise. We now know that they are considerably more severe than was then envisioned.

With regard to evolvability, genetic studies have shown that humans began to separate not long after their appearance. There are no known differences in Language Faculty, which must have already been in place. Furthermore, there is no meaningful evidence of symbolic activity prior to emergence of Homo sapiens (modern humans). These facts suggest that language emerged pretty much along with modern humans. If so, we would expect that the basic structure of language should be quite simple, the result of some relatively small rewiring of the brain that took place once and has not changed in the brief period since. The apparent contradiction with learnability therefore becomes even sharper.

Research on language acquisition has extended the dilemma further. It has shown that a child of two or three years old has largely mastered basic properties of its language, including some remarkable ones. Furthermore, statistical study of the data actually available to a child shows that relevant evidence is very sparse. These discoveries seem to require that UG must be very rich in order to overcome the enormous gap between data available and knowledge attained, while the evolvability condition demands that UG be very restricted. And the problem of apparently endless variation lurks in the background.

In the past few years, some hope has emerged to resolve this tangle of dilemmas, within the so-called minimalist program. We can see how by looking at a fundamental and quite puzzling universal property of language: structure-dependence.

Consider the properties of this simple sentence, mastered by two-year-old children as experiment has shown:

(1) The boy and the girl are in the room.

Not “is in the room”.

That raises puzzles. To determine agreement, the child does not use the simplest computational rule, adjacency. Instead, the child reflexively relies on something it never hears: the structure its mind creates. The child then assigns plurality by virtue of the nature of this abstract structure.

The problem quickly extends. Let me take the sentences below as example:

(2) a. The friend of my brothers was happy.

b. The friends of my brother were happy.

To decide whether to use was or were, we ignore linear adjacency and attend only to the structure, the Noun Phrase subject. But we have to go beyond to find the central element of the Noun Phrase, friend/friends, the more remote Noun. That turns out to be a non-trivial computation, far more complex than linear adjacency, which is reflexively ignored.

Let’s take it a step further. Consider the sentence “The mechanic who fixed the car carefully packed his tools”. It is ambiguous, “fixed the car carefully” or “carefully packed his tools”. Now put the adverb “carefully” in the front: “Carefully, the mechanic who fixed the car packed his tools?” It is now unambiguous. It means that he carefully packed his tools. The adverb carefully seeks a verb, but it cannot use the simplest computation: pick the linearly closest verb. UG forces us to ignore that simple computation and to select the more remote verb—which happens to be the structurally closest verb as we see when we assign the structure in what our minds tell us is the correct way.

It goes without saying that none of this can possibly be learned.

There is supporting neurolinguistic evidence. Experimental work shows that if subjects are presented with invented languages modelled on actual ones, the language areas of the brain react normally; but if the invented languages use very simple rules involving linear order, there is diffuse activity in the brain, indicating that it is being treated as a puzzle, not activating the language areas.

We therefore have a serious puzzle. The infant ignores 100% of what it hears—linear order—and attends only to what it never hears, abstract structures that its mind constructs. Furthermore, this is true for all constructions in all languages.

The only plausible answer is that linear order is simply not available to the child who is acquiring a system that constructs thoughts. Why then does speech require linearization? The reason is obvious. The articulatory system cannot produce structures, so the externalization process must impose linear order on an internal system of generation of thought, which is unordered. Sign language is less strictly linear because of wider options available in visual space.

The sensory-motor systems used for externalization have nothing to do with language; they were in place long before language emerged, and have not changed since. True language is the internal system that generates thought, the I-language—internal to an individual, coded as a recursive generative procedure in the brain.

We now face the question why the infant reflexively ignores 100% of what it hears—linear order—and attends only to what it never hears—abstract structures constructed by the mind.

We’ve recently discovered that there is a straightforward answer. Satisfaction of the Basic Property requires a computational procedure. The simplest procedure is binary set-formation, called “Merge” in recent work. It is easy to show that if recursive generation is based on Merge, then structure-dependence is imposed and there is no linear order. In this respect, language conforms to the miracle creed, and seeks the simplest solution.

There are many consequences. One consequence is that certain thoughts become inexpressible in speech, even very simple ones. To illustrate, let’s shift from conjunction to disjunction. Take the sentences “Either John or Mary is in the room” and “Either the girls or the boys are in the room”. How about “Either the girls or John [is or are] in the room”? Neither is possible. The thought is clear, and if number agreement were based on adjacency it could be easily expressed. But with structure-dependence, the thought is inexpressible in the simplest way, because of the internal conflict within the disjunction.

This is one of many examples of conflict between optimal design and utility for communication. There are many others that are far more serious than this one. They are always resolved the same way: communicative efficiency is always sacrificed. To put it metaphorically, when Mother Nature was constructing language, she was concerned with optimal design, not how the system might be used. If it turns out to be dysfunctional, so be it.

It’s worth noting that that’s how evolution works quite generally. We can distinguish three stages in normal evolutionary change. The first stage is innovative. Some disruption takes place, maybe mutation or gene transfer or a bacterium accidentally swallowing some microorganism, leading to eukaryotic cells, the basis for complex life. The disruption introduces something new. Then comes the second stage, reconstruction: nature re-designs the new system in the simplest way, satisfying natural law. These are matters discussed in depth in classic work of D’Arcy Thompson on laws of growth and by Alan Turing on creation of patterns by physical law. It is the miracle creed once again. The final, third stage of evolution is winnowing: natural selection reduces the variety to the better adapted. The simplest solution produced at the second stage might turn out to be dysfunctional, but nature doesn’t care. In reconstruction, nature seeks optimal design. It has no way to consider possible functions.

Language seems to fit the normal pattern. We can envision an evolutionary scenario that looks something like this. Some small rewiring of the brain yielded the general property of recursive generation. Nature then took the usual course of seeking the simplest such operation, relying on natural law (in this case, principles of computational efficiency, since we are dealing with a computational system). The result is a system based on Merge, which satisfies the Basic Property. The deepest and most surprising property of language, structure-dependence follows at once, with its ramified consequences. UG encodes the outcome. The infant therefore reflexively ignores everything it hears and attends only to the abstract structures its mind creates, fleshed out as thoughts.

In these terms, we can envision a resolution of the conundrum facing UG: the diversity condition (iii) can be put to the side in the study of the core system of generation of thought. The variety of languages might be localized largely in peripheral aspects of lexicon and in externalization; perhaps completely localized there, we might someday learn. Research seems to me to be tending in that direction, and it would be a natural outcome. The poverty of stimulus (POS) conditions on the core system are severe, sometimes clearly insurmountable, as in the case of structure-dependence. Furthermore, the Sensory-motor (SM)/I-language relation poses a cognitive problem that can be solved in many ways. It would not be surprising to find that it is the locus of the complexity and mutability of language along with their variety of languages—all superficial if these ideas are on the right track.

If so, at least for I-language, the conundrum is largely reduced to satisfying the evolvability condition (ii). That problem will be overcome to the extent that the structures of I-language are generated by the simplest operations. The Strong Minimalist Thesis (SMT) sets this outcome as a prime goal of the theory of language. The assumption again is that language conforms to the miracle creed along with the rest of nature in its core property of construction of thought.

These observations reinforce the traditional view that language is essentially a system of thought. The modern doctrine that language is basically a system of communication that may have evolved from animal communication that seems quite untenable.

Returning to the evolutionary scenario, the third stage, the winnowing stage apparently has never been reached, though it seems to be no diversity. Possibly that’s true, because the time has been so short, more interestingly, because the system is so tightly integrated that it’s either all or none. That seems to be increasingly what we find when we investigate more complex cases.

5. Words and objects: A “Speech Act” perspective

Instead of going on to further cases of genuine explanation, let’s turn to how thoughts are fleshed out.

I-language is a computational system. Any such system has primitive elements—atoms of computation—and computational procedures to form new elements.

For language, the primitives are the minimum “meaning-bearing” elements. In an analytic language like English, these are often words, so you have major books with titles like Words and Objects (W. V. Quine) or Words and Things (Roger Brown). For language generally, word is not the right concept, even for English if we look closely, but let’s keep to that.

The titles of the books reflect the standard view that words are linked to mind-external objects by the relation of reference: words refer to things in the world. For the sciences, establishing such a relation is a norm. When scientists speak of Uranium or genes, they hope there are such things. It also seems that animal communication systems observe these conditions, with a 1-1 relation between the signals, say a monkey call, and some physically identifiable event. But there is very strong evidence that human language does not observe the referential doctrine. We of course do use words to refer. That is an action, what the British philosopher John Austin called a speech act. When we look closely at the meanings of words, it is hard to sustain the idea that there is a word-object relation.

Take a standard example in the philosophical literature, a supposedly, logically proper name, like London. I can perfectly well say that I’m going to visit London again after it was destroyed by fire and rebuilt 50 miles up the Thames with different materials and design. No one believes that there is a real-world entity with such properties as these. The word London is not a proper name, it’s a city name, and our mental concept city has rich and complex properties, carried over when we use the word London in the speech act of referring.

The observation generalizes to the whole vocabulary. The basic point was recognized by Aristotle. Aristotle discussed the word house. He observes that house is an amalgam of matter and form. The material part is what a physicist could identify: bricks, timber, and so on. The form is a mental construction: the design, the intention of the architect, the characteristic use, and so on. Something could look exactly like where I live but not be a house, could be a library, could be a garage, could be a paperweight for a giant. These are not properties determined, detectable by physical examination.

Even earlier, a similar point was made by the Greek philosopher Heraclitus when he asked how we can cross the same river twice, though its material component has changed. It’s a deep question. A little thought shows that under radical material changes it remains the same river, while under slight changes it might not be a river at all, could be a canal, or with a hardened surface, could even be a highway. That turns out to be true of even the simplest words that we use to refer.

These features of language and thought raise new conundrums. All of this must be known without learning, and correspondingly seems to be shared cross-linguistically in fundamental respects. Studies of language and language acquisition have shown that these items are acquired on very few presentations, implying that they are based on rich innate structure. Learning is apparently a matter of settling relatively superficial properties. There are no significant analogues to such concepts in animal symbolic systems. Of course, we have no record of their development.

For these reasons, the origin of human concepts has seemed a hopeless mystery, buried deep in the pre-history of homo sapiens. But on reflection, that seems most unlikely. The rich and intricate concepts that are the atoms of computation would have no function outside of a system of generation of thought that yields complex expressions that can enter into reasoning, reflection, and other mental acts. If they had emerged before language, they would have been useless waste and would have been discarded. So, it is reasonable to suppose that when the capacity emerged for recursive generation of thought, it appropriated a lexicon of very elementary concepts available to proto-humans; and only later, as the combinatorial possibilities of generating language and thought became available, concepts of the distinctive human character appeared—how, we can only guess, but at least it might be possible to explore the question.

Here again the role of the Strong Minimalist Thesis (SMT) might appear. When some innovation appears, nature seeks the simplest way to accommodate it. The simpler the factors that do so, the more refined will be the system that is produced. With many factors intervening the result is likely to be chaotic. It is not too much of a stretch of the imagination to think that the simplicity and discipline of the Strong Minimalist Thesis had a significant role in the development of these unique conceptual resources of human thought. As more is being learned about the rich, inventive, creative lives and complex social orders of the tens of thousands of years of human history that are now becoming accessible to inquiry, new and helpful insights into these questions might be coming into view. It will be exciting cross-world.

6. Concluding remarks: Understanding ourselves and the shared future of human being

Following these paths, we may hope to gain real insight into the nature of language and thought, fundamental features of the human capacity. Fundamental, but of course not all inclusive. When we look around us, we see other striking features of this strange creature that recently appeared on earth, those features I alluded to at the outset, having to do with the existential crises that we face and must overcome soon.

The issue arose with dramatic clarity 77 years ago, on Aug. 6th, 1945. On that day, we learned that human intelligence had reached the level where it had found ways to destroy us all—actually not quite yet, but it was clear that science would soon reach that point. And it did, in 1952, when the US exploded a thermonuclear weapon, soon followed by the Soviet Union.

That raised a profound question about human nature: can our moral capacity rise to the level where it will control our capacity to destroy? The record of the years that follow is not encouraging, not just with regard to nuclear weapons. It was not known in 1945, but the world was entering into a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene, an epoch in which human activity has a grave impact on the environment, so serious that it imperils the survival of organized human life on earth, not to speak of the vast number of species that we are wantonly destroying.

The World Geological Organization has dated the onset of the Anthropocene to the period after World War II, when the destruction sharply escalated—By now, it has reached the level where irreversible tipping points are in sight.

The question has only become more stark over the years. There is a gap between the human capacity to destroy and human moral capacity to control their impulse. Can that gap be overcome? We will soon find out, and if it’s the wrong answer, nothing else is gonna matter.

编排:韩 畅 审稿:王 飙 余桂林

相关工具