318 阅读 2020-02-06 10:40:52 上传

Ultrasound+corpus study of phonetically-motivated

variation in North American French and English

Jeff Mielke and Christopher Carignan

North Carolina State University

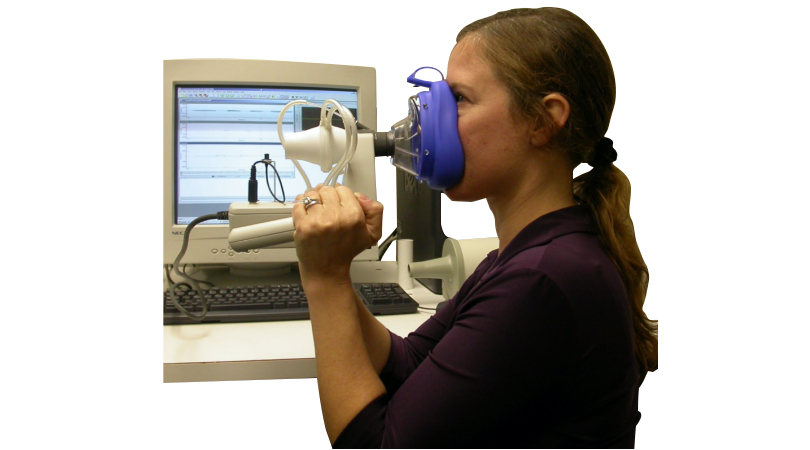

This presentation reports two projects employing ultrasound imaging to augment conversational speech corpora of French from Gatineau, Quebec, and English from Raleigh, North Carolina. Targeted articulatory data are collected in order to study phonetically-motivated sound changes in progress. While phonetically-motivated change from below is a fundamental concept in contemporary approaches to phonology and variation, empirical data is sparse (Cedergren, 1973; Trudgill, 1974; Labov, 2001), partly because changes usually go unnoticed until long after their inception, and because articulatory data on changes in progress (which can shed light on phonetic motivations) is often unavailable (cf. Scobbie et al. 2008).

The Gatineau project investigates the development of rhotic vowels in Canadian French. Some young speakers of Canadian French in Southwestern Quebec and Eastern Ontario produce the vowels /ø/, /œ/, and  making them sound like English

making them sound like English  (i.e., heureux, docteur, and commun sound like

(i.e., heureux, docteur, and commun sound like

When asked, native speakers are completely unaware of the difference between rhotic and non-rhotic pronunciations, suggesting that rhoticity is a change from below. Previous reports of retroflex-sounding variants of Canadian French vowels date back to the early 1970s in Montreal (Dumas 1972, 100, Sankoff, p.c.), and a retroflex-sounding variant of /R/ has also been observed (Sankoff and Blondeau, 2007). This change is of special interest because it resembles North American English

When asked, native speakers are completely unaware of the difference between rhotic and non-rhotic pronunciations, suggesting that rhoticity is a change from below. Previous reports of retroflex-sounding variants of Canadian French vowels date back to the early 1970s in Montreal (Dumas 1972, 100, Sankoff, p.c.), and a retroflex-sounding variant of /R/ has also been observed (Sankoff and Blondeau, 2007). This change is of special interest because it resembles North American English , which can be produced with various tongue shapes, including bunched and retroflex variants (Delattre and Freeman, 1968), raising the question of whether French rhotic vowels are also produced with these categorically different tongue shapes.

, which can be produced with various tongue shapes, including bunched and retroflex variants (Delattre and Freeman, 1968), raising the question of whether French rhotic vowels are also produced with these categorically different tongue shapes.

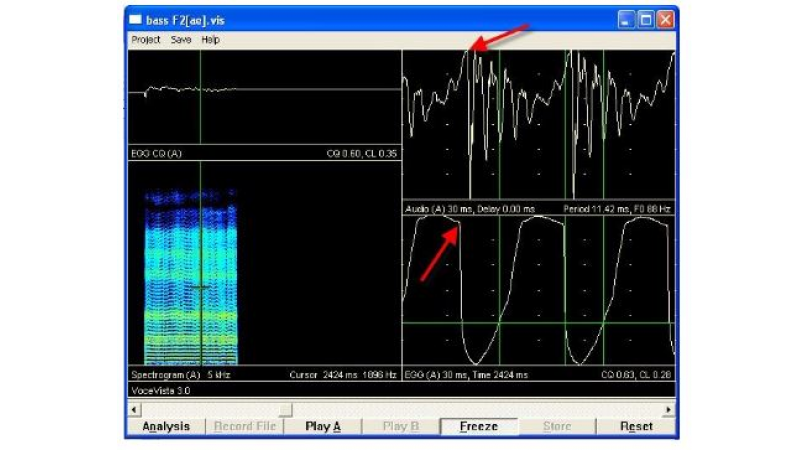

The historical development and distribution of rhotic vowels were investigated by acoustic analysis of data from 75 speakers born between 1893 and 1991, from two corpora of Ottawa-Hull French: Corpus du français parlé à Ottawa-Hull (Poplack, 1989) and Corpus du fran¸cais de l’Outaouais au nouveau millénaire (Poplack and Bourdages, 2010). Reduction in F3 values (i.e., rhoticity) for word-final /ø/ and /œ!/ was observed for speakers born after 1960 (Figure 1, left). Rhotic /œ/ before /&/ appears somewhat later. Importantly, F3 lowering (~rhoticity) emerged gradually, beginning in speakers born after 1965, and rhoticity was preceded by F2 lowering (~tongue retraction or lip rounding).

Mid-sagittal ultrasound data from 23 native speakers of Canadian French revealed that the most rhotic speakers use bunched and retroflex tongue shapes at rates comparable to those seen for English in similar contexts. Moderately rhotic vowels were produced with tongue shapes ranging from bunched to vowel-like. Figure 1 (right) shows examples of tongue shapes for two extremely rhotic speakers. One young speaker who produced extremely rhotic vowels produced them with retroflex tongue shapes, suggesting that the retroflex tongue posture emerged only after the change progressed to the point where the perceptual target was extreme enough to motivate a learner to use a non-vowel-like tongue posture.

in similar contexts. Moderately rhotic vowels were produced with tongue shapes ranging from bunched to vowel-like. Figure 1 (right) shows examples of tongue shapes for two extremely rhotic speakers. One young speaker who produced extremely rhotic vowels produced them with retroflex tongue shapes, suggesting that the retroflex tongue posture emerged only after the change progressed to the point where the perceptual target was extreme enough to motivate a learner to use a non-vowel-like tongue posture.

The second project draws participants directly from a 200-speaker corpus of Raleigh, NC English (Dodsworth and Kohn, 2012). Data collection for this project is still in progress. The variables under investigation are /æ/ tensing, postlexical / s/-retraction, flapping, intrusive [l], /l/ vocalization, and pre-liquid vowel changes. While these variables differ in their salience, they are all expected to be sensitive to inter-speaker articulatory variation in tongue and velum movements.

flapping, intrusive [l], /l/ vocalization, and pre-liquid vowel changes. While these variables differ in their salience, they are all expected to be sensitive to inter-speaker articulatory variation in tongue and velum movements.

References

Cedergren, Henrietta. 1973. The interplay of social and linguistic factors in Panama. Doctoral Dissertation, Cornell University.

Delattre, Pierre, and Donald C. Freeman. 1968. A dialect study of American r’s by x-ray motion picture.Linguistics 44:29–68.

Dodsworth, Robin, and Mary Kohn. 2012. Urban rejection of the vernacular: The SVS undone. LanguageVariation and Change 24:221–245.

Dumas, Denis. 1972. Le fran¸cais populaire de Montréal: description phonologique.Universit´e de Montréal M.A. thesis.

Labov, William. 2001. Principles of linguistic change: Social factors. Oxford: Blackwell.

Poplack, Shana. 1989. The care and handling of a mega-corpus. In Language change and variation, ed.Ralph Fasold and Deborah Schiffrin. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Poplack, Shana, and Johanne S. Bourdages. 2010. Normes et variation en français : Rivitalité entre l’école, la communauté et l’idéologie. Research project funded by SSHRC (# 410-2005-2108 [2005-2008]), Ottawa, Ontario.

Sankoff, Gillian, and Hélène Blondeau. 2007. Language change across the lifespan: /r/ in Montreal French. Language 83:560–588.

Scobbie, James, Jane Stuart-Smith, and Eleanor Lawson. 2008. Looking variation and change in the mouth: Developing the sociolinguistic potential of ultrasound tongue imaging. Unpublished Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) end of grant report, Swindon, U.K.

Trudgill, Peter, ed. 1974. The social differentiation of English in Norwich. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.